Supplying the Means for Repression in Belarus

Transfer of crowd-control weapons (mis)used to crack down on human rights

- by

- 20 December 2021

FIDH releases a briefing paper analysing foreign-made less lethal weapons and firearms employed by the Belarusian security forces to crack down on peaceful protesters, provides an overview of their procurement and application, and outlines possible avenues for state and corporate accountability.

Download the report:

Since August 2020, Belarusians have systematically taken to the streets throughout the country to protest election fraud. Although overwhelmingly peaceful, these public assemblies have been violently dispersed by the authorities. Law enforcement officials, equipped with shotguns and pistols, rubber bullets and batons, stun grenades and chemical irritants, among others, used deliberate, unnecessary and indiscriminate force against participants at rallies: women, minors, and even the elderly and persons with disabilities, resulting in injuries to hundreds of individuals and four confirmed deaths.

Civil society has documented the use of rubber bullets, light and sound cartridges, tear gas and other ammunition suggesting the use of weapons manufactured in Russia, Turkey, United States, and European Union (EU) countries. In addition, officers of special law enforcement units were equipped with foreign-made firearms which might have been exported to Belarus in violation of the 2011 EU arms embargo and other international regulations.

“Human Rights Center "Viasna", and other civil society organizations, have documented penetrating gunshot wounds, fractured bones, loss of eyesight and other serious injuries,” remarks Pavel Sapelka, lawyer of the HRC Viasna, FIDH member organization in Belarus. “The violent attacks against peaceful protestors are an unacceptable restriction of the right to peaceful assembly and the right to freedom of expression. It is important that the Lukashenko regime does not benefit from any direct or indirect support of violence from abroad, whether from states or private companies” - notes Sapelka.

The briefing paper analyses crowd-control weapons and firearms employed by the Belarusian security forces to crack down on peaceful protesters, as well as their origin and transfer, and briefly outlines possible avenues for state and corporate accountability. Specifically, it details the applicable legal framework for the use and transfer of crowd-control weapons and firearms, identifies the types of weapons used, including their manufacturer, country of origin and transfer state, provides a brief analysis of whether their transfer violates the applicable law, and points to potential state and corporate accountability.

“Our report shows that states and corporations abuse the porous legal regime on the transfer of less lethal weapons to continue delivering tear gas, stun grenades, rubber bullets, and other equipment that is used to crack down on peaceful protesters in Belarus, despite knowing that these weapons will be used to crush dissent”, said Ilya Nuzov, Head of the Eastern Europe and Central Asia desk.

A chilling recording of Deputy Minister of Internal Affairs Nikolai Karpenkov calling on security forces to «use your weapon and shoot [the protester] right in the forehead, right in the face», which has leaked to the press, confirms the deliberate, systematic character of police violence against peaceful protesters, coordinated at the highest political levels.

“Both states and corporations should cease delivery of the means for repression in Belarus or face consequences for facilitating repression to the extent they violate international law”, concludes Ilya Nuzov.

READ FULL TEXT

BACKGROUND

TERMS AND DEFINITIONS

1. INTERNATIONAL LEGAL FRAMEWORK

1.1. The right of peaceful assembly

1.2. Policing of assemblies

1.3. Trade control in law enforcement equipment

2. THE MISUSE OF FIREARMS AND CROWD-CONTROL EQUIPMENT

2.1. Firearms

2.2. Kinetic impact projectiles

2.3. Riot control agents

2.4. Stun grenades

2.5. Water cannons

3. ACCOUNTABILITY PROSPECTS

3.1. Transfers violating international obligations and the EU embargo

3.2. Responsibility for human rights violations

RECOMMENDATIONS

BACKGROUND

On 9 August, final voting was held in the 2020 presidential elections in Belarus, which was preceded by over 1,300 arbitrary arrests of activists and several opposition candidates. Despite numerous confirmed irregularities and lack of transparency in the voting process, the preliminary results awarded the victory to incumbent President Alexander Lukashenko with 80% of the popular vote. Opposition candidate Svetlana Tikhanovskaya, who claimed the victory for the opposition, reportedly came in second with only 10% of the vote. These results were not recognized by the international community.

Large protests erupted immediately following the announcement of election results. Since August 2020, people have systematically continued to take to the streets throughout the country. Although overwhelmingly peaceful, these public protests have been violently dispersed. Law enforcement officials, equipped with shotguns and pistols, rubber bullets and batons, stun grenades and chemical irritants, among others, used unnecessary and excessive force against protesters resulting in injuries to hundreds of individuals and four confirmed deaths. A recording of Deputy Minister of Internal Affairs Nikolai Karpenkov calling on security forces to «use your weapon and shoot [the protester] right in the forehead, right in the face», which has leaked onto the Internet, confirms the deliberate, systematic character of police violence against peaceful protesters, coordinated at the highest political levels.

After violent dispersals of the protests, journalists and civil society organisations documented, used ammunition cartridges with rubber bullets, light and sound cartridges and other ammunition that was employed against the protesters manufactured for the most part in Russia and European Union (EU) countries. In addition, the officers of special law enforcement units were equipped with foreign-made firearms which might have been exported to Belarus in violation of the 2011 EU arms embargo and other international obligations.

This briefing paper analyses crowd-control weapons and firearms employed by the Belarusian security forces to crack down on peaceful protesters, as well as their procurement and application, and briefly outlines possible state and corporate responsibility. Specifically, section 1. details the applicable legal framework for the use and transfer of crowd-control weapons and firearms. Section 2. identifies the types of weapons used, including their manufacturer, country of origin and transfer state, and section 3. provides a brief analysis of whether their transfer violates the applicable law and points to potential state and corporate responsibility.

TERMS AND DEFINITIONS

CROWD-CONTROL WEAPONS

Crowd-control weapons (CCWs) also known as “riot-control weapons,” “non-lethal,” “less lethal,” or “less than lethal” weapons. CCWs include chemical irritants, kinetic impact projectiles, acoustic weapons, water cannons, stun grenades, and other equipment used in policing public assemblies with the exception of lethal weapons such as firearms.

DUAL-USE ITEMS

Goods and technologies are considered to be dual-use when they can be used for both civil and military purposes, such as special materials and chemicals, sensors and lasers, high-end electronics, marine and nuclear equipment, etc. The EU dual-use list includes a range of chemicals used by law enforcement personnel for public assembly management.

EXPORT CONTROL

The term ‘export control’ or else ‘trade control’, as used in this publication, refers to the current practice relating to controls on export, import, brokering, transit, shipment, technical assistance as pertains to arms and dual-use items.

KINETIC IMPACT PROJECTILES

Kinetic impact projectiles (KIPs), commonly known as rubber and plastic bullets, are used for crowd control purposes by law enforcement and are shot from myriad types of guns and launchers, including lethal arms.

LESS LETHAL WEAPONS

The publication employs the term ‘less lethal weapons’ as synonymous to CCWs to designate a wide array of weapons used in policing public assemblies. The term ’less lethal’ is preferred over ‘non-lethal’ since the use of such weapons can have fatal consequences.

MILITARY USE ITEMS

Goods and technologies are classified as military goods if they are designed specifically for military use, such as small arms, armed vehicles and protective equipment.

RIOT CONTROL AGENTS

Riot control agents (RCAs) are toxic chemicals designed to deter or disable, by producing temporary irritation of the eyes and upper respiratory tract. The most frequently used RCAs include CN or CS (commonly called tear gas) and OC/Pepper or PAVA (commonly called pepper spray).

SMALL ARMS

Small arms are, broadly speaking, weapons designed for individual use. They include, inter alia, revolvers and self-loading pistols, rifles and carbines, sub-machine guns, assault rifles and light machine guns. The terms ‘small arms’ and ‘firearms’ are employed as synonymous throughout the publication.

1. INTERNATIONAL LEGAL FRAMEWORK

The use of less lethal weapons and other law enforcement equipment often results in deaths and injuries that, depending on the circumstances, might amount to violations of the right to life, the right to freedom from torture and other forms of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, the right to health, the right to peaceful protest - freedom of assembly, and have an impact on other human rights.

– 1.1. The right of peaceful assembly

Freedom of peaceful assembly is a fundamental right that is protected by the Belarusian Constitution and international human rights law instruments, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), ratified by Belarus, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and commitments undertaken by Belarus within the framework of the Organisation for the Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). States have a positive obligation to protect and promote the right of peaceful assembly, must not interfere with peaceful assemblies and should not, a fortiori, prohibit, restrict, block or disperse peaceful assemblies without compelling justification.

All assemblies must be presumed to be peaceful, and separate acts of violence by some protesters should not serve as grounds for dispersal. Those individuals who engage in violent actions may fall outside the scope of the protection provided by the right to peaceful assembly but continue enjoying other human rights, in particular freedom from cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment and the right to life. Dispersal may only be considered where violence is serious and widespread, and where law enforcement officials have exhausted all reasonable measures to facilitate the assembly and protect participants.

These international norms are being violated in Belarus, where law enforcement personnel have been dispersing protests without compelling justification on the basis that the assemblies were “non-authorized”. According to the Belarus law on public assemblies, assemblies require prior authorization, which is often denied, if not held in places designated by the authorities. As follows from the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) General comment No. 37 on the right of peaceful assembly (article 21 of the ICCPR), its exercise should not depend on prior authorization by the authorities.

The UN Code of Conduct for Law Enforcement Officials (1979) stipulates that law enforcement officials “may use force only when strictly necessary and to the extent required for the performance of their duty”. The UN Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials (the Basic Principles, 1990) specify that “law enforcement officials, in carrying out their duty, shall, as far as possible, apply non-violent means before resorting to the use of force and firearms [...]. Whenever the lawful use of force and firearms is unavoidable, law enforcement officials shall exercise restraint in such use and act in proportion to the seriousness of the offence and the legitimate objective to be achieved”. The principles laid down in these documents remain fundamental to policing assemblies around the world.

Whereas the Basic Principles encourage states to develop less lethal weapons for law enforcement officers in order to offer a less-dangerous alternative to lethal weapons, it is now proven that less lethal weapons and related equipment may kill, injure, and inflict torture. There’s a vital need for their use to be rigidly controlled: only weapons that have been tested and present a lower risk can be used, and even then with caution and by specially trained officers.

In 2014, Resolution 25/38 of the UNHRC encouraged states “to make protective equipment and non-lethal weapons available to their officials exercising law enforcement duties, while pursuing international efforts to regulate and establish protocols for the training and use of non-lethal weapons”. In 2018, the UNHRC further encouraged the establishment of protocols "for the training and use of non-lethal weapons, bearing in mind that even less lethal weapons can result in risk to life".

Then-Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, Juan E. Méndez, stressed that depending on the seriousness of the pain and the inflicted injury, “excessive use of force may constitute cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or even torture”. In a similar vein, the European Court of Human Rights emphasized that the use of physical force against a person, when it is not strictly necessary because of his conduct, violates human dignity and constitutes in principle a violation of the right guaranteed by Article 3" [of the European Convention on Human Rights].

To reflect these developments, the 2020 United Nations (UN) Guidance on less lethal weapons in law enforcement only allows “the use of less lethal weapons to disperse an assembly” as “a measure of last resort”; similarly, “any use of force by law enforcement officials shall comply with the principles of legality, precaution, necessity, proportionality, non-discrimination and accountability”. In addition, the Guidance calls for, among others, testing independent from the manufacturer and a legal review of less-lethal weapons before their deployment.

In the context of generally peaceful protests, the use of indiscriminate less lethal weapons, such as tear gas, stun grenades, and water cannons, is a priori illegal. The use of firearms to disperse an assembly is always unlawful.

In line with international standards, law enforcement officials have a duty “to distinguish between those individuals acting violently and other assembly participants”. In situations where some force is necessary, “less lethal weapons [...] shall target only individuals engaged in acts of violence.” The Guidance specifies that the weapons such as tear gas, which is not accurate in principle as it is dispersed at a distance, "should be targeted at groups of violent individuals unless it is lawful in the circumstances to disperse the entire assembly”. It follows that in the context of generally peaceful protests, as it was the case in Belarus, the use of indiscriminate less lethal weapons, such as tear gas, stun grenades, and water cannons, is a priori illegal. The 2020 Guidance provides that “the use of firearms to disperse an assembly is always unlawful”.

The subsequent chapters of the report contain documented evidence of illegal, unnecessary and disproportional use of force against peaceful protesters by the Belarusian law enforcement. The FIDH cites examples of the use of lethal weapons, in conjunction with less lethal ammunition, leading directly to injuries and fatalities, in flagrant violation of international human rights standards.

– 1.3. Trade control in law enforcement equipment

The Belarusian regime has a long history of human rights abuses by the police, military and law enforcement institutions. Trading arms with such a regime should therefore be considered highly problematic, as transfers are likely to result in the use of such arms to commit serious violations of human rights. In addition to the obligations of companies and states under general international law, arms and security equipment trade is subject to a number of regulations that may prohibit trade or require export controls depending on a number of factors, such as the type of weapon and the human rights record of the importing country. The applicable regime is complex, with occasional overlaps and gaps.

On a global level

Only a limited range of equipment used by law enforcement is subject to international export controls. However, trade in firearms, such as shotguns and pistols, is regulated more effectively under a range of international and regional legal regimes as compared to less lethal weapons. Trade in most of the less lethal weapons and related munitions is not regulated at the international level.

On the global level, firearms trade is regulated in a series of agreements most prominent of which is the Arms Trade Treaty (2014, ATT). ATT prohibits adhering states from granting exports authorisations for conventional arms if the transferred items would be used in the commission of genocide, crimes against humanity, grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions of 1949, attacks directed against civilian objects or civilians protected as such, or other war crimes as defined by international agreements to which it is a Party. Furthermore, Article 7 of the ATT prohibits transfers in case they risk to “commit or facilitate a serious violation of international human rights law”. Though there is a certain latitude on the state level as to which weapons to include in national control lists, revolvers and self-loading pistols, rifles and carbines, assault rifles, sub-machine guns, and light machine guns designed for military use, certainly fall within the scope of the treaty.

According to the ATT Monitor 2016 Report and the ICRC, less lethal weapons such as plastic and rubber bullets, as well as tear gas, fall within the scope of the ATT, as they have potentially lethal consequences as long as they are ‘fired, launched or delivered’ by small arms, so are within the purview of Article 3. This opinion, which is not shared by all States parties, reflects the encouragement in Article 5.3 to apply the provisions of the Treaty ‘to the broadest range of conventional arms’.

110 countries are party to the treaty and another 31 have signed it, however, such major arms exporters as the US and Russia have not ratified the ATT, nor has Belarus.

Since 2003, members of the Wassenaar Arrangement (WA) are also obliged to maintain rigorous national export control systems over the trade in conventional arms and dual use items. Guidelines approved on the WA plenary in 1998 require participating states to assess risks of “the violation and suppression of human rights and fundamental freedoms” before granting export authorisations. The WA List of Dual-Use Goods and Technologies and the Munitions List notably covers smooth-bore weapons with a calibre of less than 20 mm, other arms and automatic weapons with a calibre of 12.7 mm (calibre 0.50 inches) or less, and accessories. This includes rifles and combination guns, handguns, machine, sub-machine and volley guns, as well as smooth-bore weapons, that is, small arms with which the Belarus law enforcement officials are equipped. Most types of RCAs widely used during the Belarus protests, notably CN, are also subject to export controls under the WA. It should be noted, however, that the WA does not cover RCAs individually packaged for personal self-defence purposes, i.e. sprays.

Whilst water cannons, stun grenades, rubber batons and some other types of less lethal weapons are frequently used in the commission of human rights violations, they seem to have escaped import and export controls set in the ATT and the WA. In this respect, it is important to highlight that the purpose of both the ATT and WA is to control equipment, specially designed or modified for military use, as opposed to law enforcement equipment.

To comply with the obligations under the ATT and the WA, before granting export authorisations the relevant national authorities shall assess the human rights situation in the destination country, among others, by consulting relevant documents from UN human rights bodies, regional human rights and civil society organisations.

According to civil society and international organisations’ reports, the human rights situation in Belarus has been increasingly alarming at least since the late 1990s., In 2004-2007, the situation has progressively deteriorated, as reflected in a series of resolutions stemming from the leading regional and international organisations. In 2004, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe adopted Resolution 1371 (2004) "Disappeared persons in Belarus” pointing at the responsibility of the state for the enforced disappearance of opposition leaders in Minsk in the late 1990’s and recalling that the crime of enforced disappearance constitutes "a grave and flagrant violation of the human rights and fundamental freedoms”. The European Union went further and, in 2006, adopted Council Regulation No 765/2006 introducing sanctions against President Lukashenko and certain officials of Belarus over violations of “international electoral standards and international human rights law. In 2007, the UN General Assembly adopted resolution 61/175 on Situation of human rights in Belarus, expressing a “serious concern relating to the deterioration of the human rights situation in Belarus”. In view of the above, the risk of misuse of arms transferred to Belarus might have been considered as “high” since, at the latest, 2006. Thus, the WA should have discouraged export authorisations to Belarus since 2006. And state parties to the ATT were prohibited from granting export authorisations since its entry into force in 2014.

On a global level, transfer of shotguns and pistols in service of Belarus law enforcement to Belarus should have been prohibited at least since 2006 under the Wassenaar Arrangement and since 2014 under the Arms Trade Treaty.

While most of the binding obligations laid down in international law are directed at states, private companies, including manufacturers of law enforcement equipment and brokering companies, also have a responsibility to respect human rights and therefore conduct their own human rights impact assessment before shipping such equipment to third countries. Under the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs), all business enterprises are required to conduct human rights due diligence processes and put in place procedures aiming at identifying, preventing, mitigating and accounting for human rights impacts caused by their operations, business relationships, products or services in any country. UNGPs recommend that private companies respect all internationally recognized human rights. The OECD Guidelines on Multinational Enterprises and the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct (OECD Guidance) provides similar recommendations to businesses operating or based in OECD countries.

On the European level

The EU Anti-Torture Regulation, which came into force in 2006, prohibits trade in goods which have no practical use other than for the purpose of capital punishment or torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment, and imposes trade controls requirements on a range of equipment that is frequently used in serious human rights violations, but that often escapes national military, dual-use, or strategic export control lists. The latter category includes widely used RCAs such as OC (pepper) spray and PAVA - a synthetic incapacitating spray similar to pepper spray. The EU dual-use export control regime equally seems to capture a range of RCAs and related equipment creating an authorisation requirement for its export. The EU Anti-Torture Regulation requires states to consider the human rights situation in the receiving State before authorising exports of other law enforcement and security weapons and equipment.

The EU trade controls pertaining to arms transfer reflect commitments agreed upon in the Wassenaar Arrangement. The EU Council 2008 Common Position (2008/944/CFSP) laying down common rules governing the control of exports of military technology and equipment, applies to items listed in the Common Military List of the European Union. Among others, the Common Military List covers shotguns, pistols, other types of small arms and related ammunition under ML 1, ML 2 and ML 3. It also applies to a wide range of explosives and chemicals, including some RCAs and their most common compounds CN and CS (tear gas).

The EU Council 2008 Common Position prohibits exports when inconsistent with international obligations and commitments of member states, in particular sanctions adopted by the UN Security Council or the EU, nonproliferation agreements as well as other international obligations. The Common Position equally forbids export “if there is a clear risk that the military technology or equipment to be exported might be used for internal repression”. As relates to Belarus, such risk was present since 2006, according with the Council Regulation No 765/2006 introducing sanctions against certain officials of Belarus, and with certainty since 2011, with the introduction of the EU arms embargo on Belarus.

Since 2008, transfer of military items to Belarus should have been prohibited under the EU Council Common Position (2008/944/CFSP) due to a clear risk that it might be used for internal repression.

In June 2011, in view of the deteriorating situation of human rights, democracy and the rule of law in Belarus, the EU strengthened the existing sanctions on the leadership of Belarus by imposing an arms embargo through Council Decision 2011/357/CFSP, implemented through Council Regulation (EU) No. 588/2011. The Decision provided, in part, that “the sale, supply, transfer or export of arms and related material of all types, including weapons and ammunition, military vehicles and equipment, paramilitary equipment and spare parts for the aforementioned, as well as equipment which might be used for internal repression, to Belarus by nationals of Member States or from the territories of Member States or using their flag vessels or aircraft, shall be prohibited whether originating or not in their territories". The Regulation specifies in its Annex III the equipment which might be used for internal repression, covering, among others, firearms which are not controlled by ML1 and ML2 of the Common Military List and related ammunition, bombs and grenades, including light and sound grenades, not controlled by the Common Military List, Vehicles equipped with a water cannon, specially designed or modified for the purpose of public assembly management, vehicles specially designed for the transport or transfer of prisoners and/or detainees, a range of RCAs.

The embargo has been repeatedly extended and is currently in effect until February 28, 2022.

Since 2011 at latest, the EU member States were prohibited from exporting to Belarus military technology and equipment, including small arms, as well as equipment which might be used for internal repression.

Since October 2020, the EU has progressively imposed new restrictive measures against Belarus. On 24 June 2021, the Council of the EU introduced measures against the Belarusian regime “to respond to the escalation of serious human rights violations in Belarus and the violent repression of civil society, democratic opposition and journalists”. The new sanctions include the prohibition, among others, to directly or indirectly sell, supply, transfer or export to anyone in Belarus equipment, technology or software intended primarily for use in the monitoring or interception of the internet and of telephone communications, and dual-use goods and technologies for military use and to specified persons, entities or bodies in Belarus.

2. THE MISUSE OF FIREARMS AND CROWD-CONTROL EQUIPMENT

In the first days after the elections in Belarus, law enforcement and military personnel equipped with firearms were involved in suppressing protests. As a general rule, street assemblies in Belarus were mainly dispersed by OMON and the officers of the GUBOPiK, units of the Ministry of the Interior of Belarus, often without any insignia on their uniforms. In addition, members of anti-terrorist units of the Ministry of Interior and the KGB of Belarus — "Almaz’’ and "Alpha," respectively, as well as soldiers of the Special Forces unit (SOBR) of the internal troops were involved in suppressing the protests. Some of the law enforcement officers wore civilian clothes, but were nevertheless armed. In addition, law enforcement officers were routinely issued handcuffs, helmets, rubber batons, and shields.,

The order to employ the military personnel during the protests was given by Major General Vadim Denisenko, commander of the special operations forces. According to media reports, he also ordered shoot to kill “if necessary”. On 12 October 2020 Deputy Interior Minister Gennady Kazakevich reiterated that the Belarus police is permitted to “use special equipment and military weapons” against protesters if needed., The law “On the Internal Affairs Bodies of the Republic of Belarus” prohibited the use of weapons during assemblies at the time. However, this unlawful practice was cemented in law “On Amendments to the Laws on Ensuring the National Security of the Republic of Belarus” which came into force on 19 June 2021. Among other provisions, it granted law enforcement the right to use military and special equipment to manage public assemblies and stipulated that officers not be liable for harm caused as a result of the use of force and weapons. The premeditated use of lethal force to disperse mostly peaceful demonstrations constitutes a blatant violation of the right to peaceful assembly and international standards on policing of assemblies.

Overall, no less than 15 citizens died as a result of the post-electoral violence against protesters in Belarus, and at least two of them, including Gennady Shutov and Alexander Tarakhovsky were shot from firearms.

Brest resident Gennady Shutov (Hienadz Shutau), 43, who received a gunshot wound to the head on August 11, died in a military hospital in Minsk during the crackdown on protests in the city. According to his medical diagnosis he had an open penetrating gunshot wound to the skull, contusion - decomposition of the brain, multi-slip fracture of the skull with a transition to the base. On August 12, 2020, the press service of the Interior Ministry of Belarus reported that firearms were used against protesters in Brest, one person was wounded. Later, the post was edited and the word "firearm" was removed from it.

Shutov was posthumously convicted “for resisting the police”. From the materials of the criminal case follows that one of the servicemen, captain of special operations forces Roman Gavrilov and warrant officer Arseniy Galitsin, shot Shutov. Both of them serve in the military unit that is stationed in Maryina Gorka. At the protests they wore civilian clothes and infiltrated the crowd with pistols.

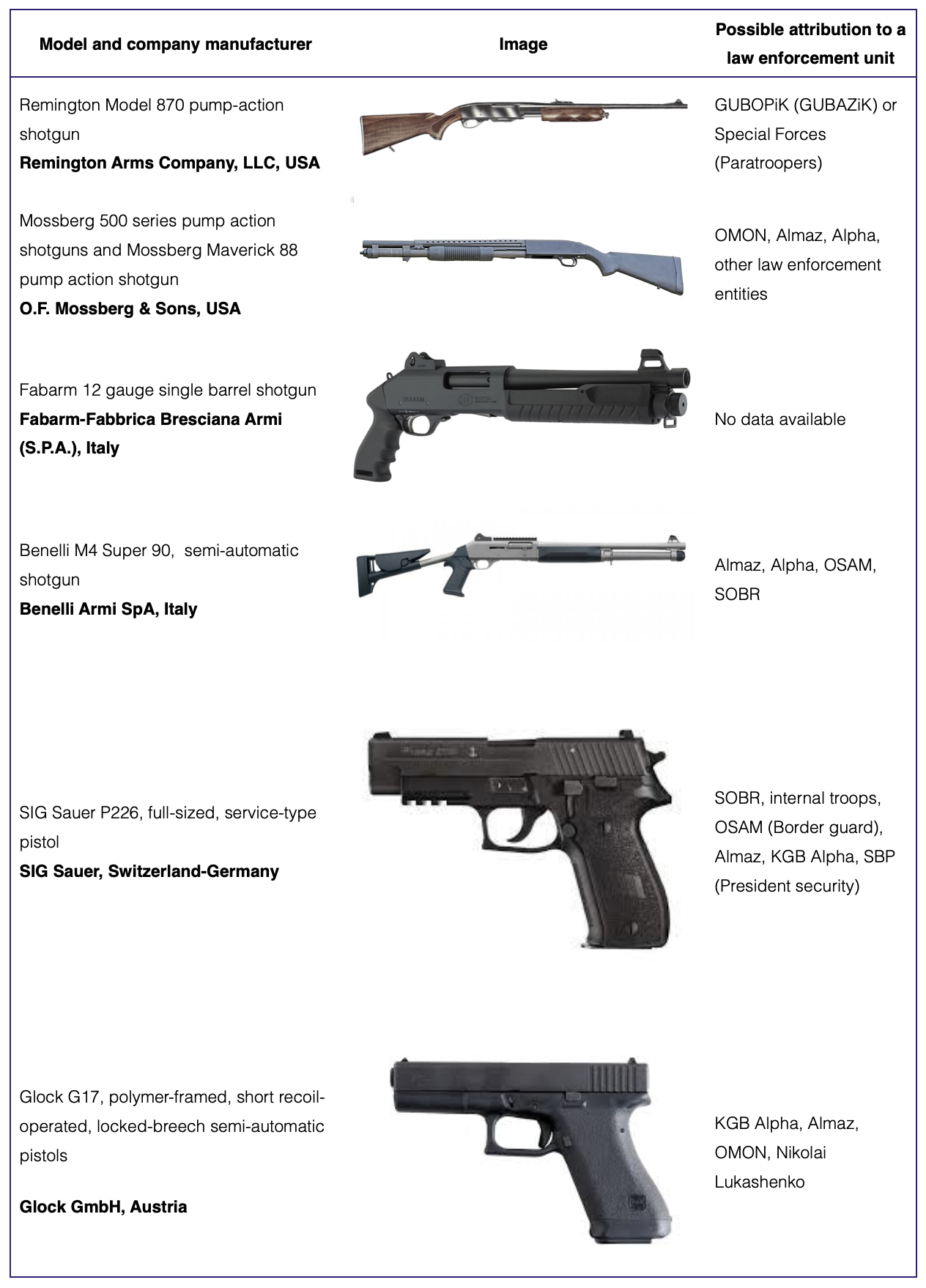

Although most of the weapons available to the law enforcement are manufactured in Belarus or in Russia, spent ammunition found after the protests seems to match, among others, with weapons imported from third countries. Notably, media and civil society organisations reports indicate that during the protests law enforcement officers carried and/or used weapons produced by Remington and Mossberg (USA),, Fabarm and Benelli (Italy), SIG Sauer (Switzerland-Germany) and Glock (Austria). Experts claim that these weapons are in regular service of the Belarusian special services.

The above firearms are lethal weapons for which less-lethal ammunition is generally available. Judging by the ammunition found after the protests, and notably, rubber and plastic bullets (please refer to the section below), the Belarus law enforcement used these weapons with less-lethal ammunition., It is not clear whether some of the above-mentioned weapons carried by the law enforcement were charged with lethal ammunition. It should be noted however, that even if firearms are used with less-lethal ammunition, the risk of use of lethal force remains high.

Table 1. Foreign-made weapons carried by the Belarus law enforcement while policing peaceful assemblies

As noted earlier, the use of firearms to disperse a peaceful assembly is always unlawful. In Belarus, the law enforcement acted in violation of international standards by using weapons against protesters unnecessarily and without precaution, causing the death of at least two protesters. By using lethal weapons against peaceful protesters without an objective necessity – the protesters did not pose a threat to the life of law enforcement officers or third persons – Belarus has also arbitrarily deprived the protesters’ right to life, in violation of Article 6 of the ICCPR.

The relevant national legislation enshrining this practice is also illegal from the point of view of international law. The threat or use of conventional weapons for repression of protests facilitates serious human rights violations committed by the Belarus law enforcement against peaceful protesters, such as violation of the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly, freedom of expression, protection from arbitrary detention, and protection from torture and inhuman treatment.

– 2.2. Kinetic impact projectiles

Evidence of disproportionate and indiscriminate use of kinetic impact projectiles (KIPs), commonly known as rubber and plastic bullets, by Belarusian security forces is recorded in medical reports, which have fallen into the hands of Belarusian journalists. Those injured during the suppression of protests on the night of August 9-10 were brought to hospitals with gunshot wounds, splinter wounds or open wounds to various parts of the body: abdomen, hips, chest, neck and so on. Independent health sources claim that from August 9 to 23, over two weekends of protests, 45 people with gunshot wounds sought medical attention at hospitals. The large number of victims indicate that the authorities used force against the crowd and from an unsafe distance, not against individual violent protesters, but indiscriminately against the crowd in an attempt to disperse the protest, which is inherently unlawful under international law.

10 August, around 10 p.m., Aleh Navahurski was with friends in the center of Baranavichy city. According to him, he joined a crowd of protesters on Komsomolskaya Streetand and decided to follow along to see what was going on. Around 11 a.m. he stumbled upon a “wall” of shields held by the law enforcers. People around him started to run, and so did Aleh. He did not think that the officers would shoot at the unarmed people, but he ran away from them with hands up. Suddenly, the police started shooting. Oleg felt almost no pain, but after he realized where the bullet hit him, he became frightened: he thought he was left without an eye. At the hospital, Aleh claimed that he fell. He was operated on and stitched up. It is still unknown whether he will be able to fully regain his vision.

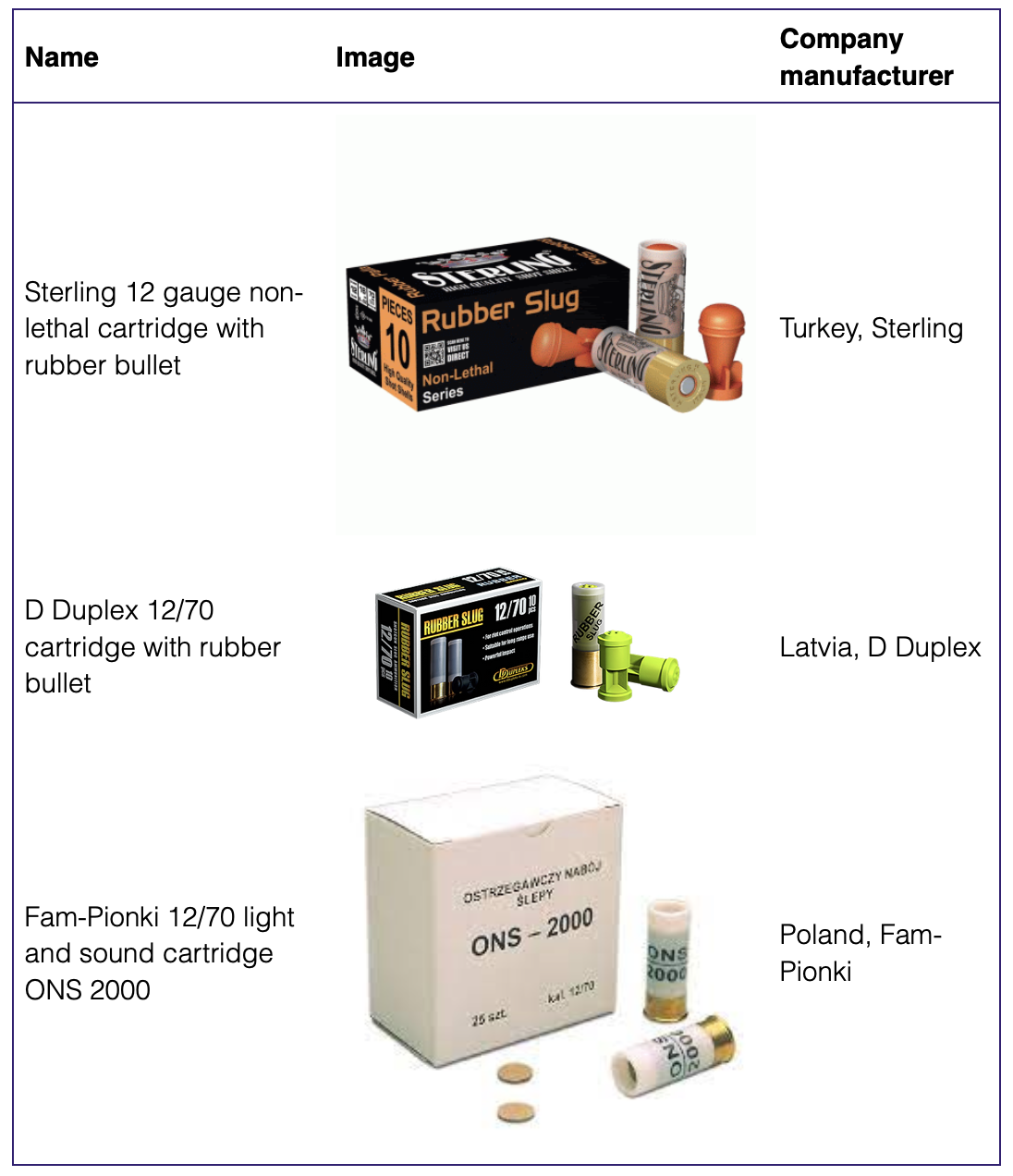

A range of KIPs were allegedly fired by the Belarus law enforcement from lethal weapons. After the crackdown on the protests in the streets of Minsk and other cities journalists found, among others, ammunition produced in third countries. Experts and journalists notably identified the following foreign-made ammunition used to suppress protests in Belarus: STERLING 12 gauge less lethal cartridge with rubber bullet (Turkey),, D Dupleks 12/70 cartridge with rubber bullet (Latvia), Fam-Pionki 12/70 light and sound cartridge ONS 2000 (Poland).

Table 2. Examples of the foreign-made less lethal ammunition found after the protests

KIPs should generally be used to target violent individuals and only with the aim of preventing an imminent threat of injury. The findings of a systematic review of medical literature carried out by Physicians for Human Rights indicate that KIPs cause serious injury, disability, and death. KIPs are inherently inaccurate when fired from afar and therefore can cause unintended injuries to bystanders and strike vulnerable body parts; at close range, they are likely to be lethal. It should be also noted that ammunition with multiple projectiles is inherently indiscriminate because it can hit unintended targets, including bystanders. Therefore, KIPs are not an appropriate weapon to be used for crowd management and specifically for dispersal purposes, as it has been done in Belarus.

In Belarus, KIPs were fired in cases where it was not strictly necessary to do so, and when non-violent means had not been exhausted, as prescribed by international standards. The use of kinetic weapons, not only rubber bullets, but also rubber batons, by the Belarusian police, in many cases amounts to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or even torture.

Riot control agents (RCAs) work by causing irritation to the area of contact (for example, eyes, skin, nose) within seconds of exposure, the effects of exposure generally do not last longer than 30 minutes. Prolonged or repeated exposure however may cause long-term effects including blindness, respiratory failure, chemical burns to the throat and lungs. Studies suggest that deployment of OC (pepper-gas) should be halted across the EU until independent research has more fully evaluated any risks it poses to health, although international standards do set out possible circumstances in which chemical irritants could be deployed.

Maina Kiai, then-UN Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association, noted that tear gas is inherently indiscriminate, making no distinction "between demonstrators and non-demonstrators, healthy people and people with illnesses”. The tear gas affects the usually peaceful majority, in violation of international standards mandating the selective disarming of violent protesters, allowing the main demonstration to continue. The European Court of Human Rights has also stated that "the unjustified use of tear gas by law enforcement officials is incompatible with the prohibition of ill-treatment.

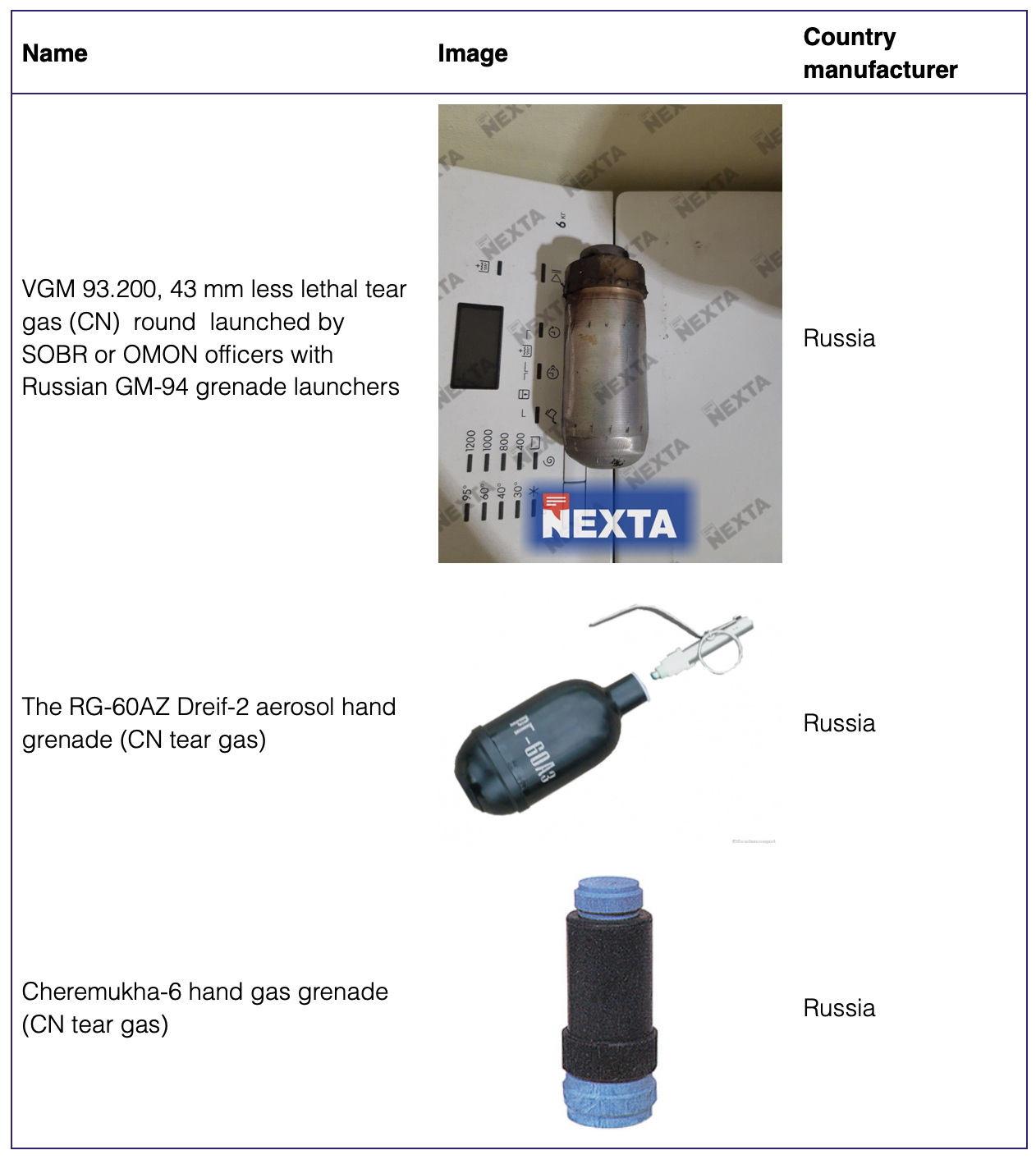

ISans has identified the following ammunition, mostly Russian-made, used by the Belarus law enforcement to spray chemical irritants: 43-mm shot VGM93.200, hand gas grenade Cheryomukha-6 with irritating effect, hand aerosol grenades "Dreyf" and “Dreyft-2”. The latter devices may cause watery eyes, sharp pain and blurred vision, blistering on skin contact.

Table 3. Examples of the foreign-made less lethal ammunition found after protests

The Belarus OMON used a range of riot control agents or chemical irritants to crack down on protesters, including tear gas and pepper spray. In most cases RCAs were delivered by firing a grenade – exposing groups of individuals to health risks without distinguishing between peaceful protesters and those acting violently and causing shrapnel wounds. Numerous reports confirm the indiscriminate and unnecessary use of chemical irritants against predominantly peaceful protesters. Many of them were admitted to hospitals with seizures, post-epileptic seizures, eye injuries, and chemical burns to the conjunctiva of the cornea, which may have been caused by the irritants.

Stun grenades, also known as light and sound grenades, unleash a bright flash and a loud bang of about 160-180 decibels. By comparison, ambulance and police sirens produce sound at 120 dB, and exposure to 150 decibels of noise at close distance can cause eardrum rupture and permanent hearing damage. A number of serious health risks are associated with the use of these weapons particularly at close range: the sound leaves individuals disoriented and can cause ear damage or post traumatic stress disorder. It also can cause severe burns, blast and shrapnel injuries, and panicked crowds can cause crush injuries. There is also a clear risk of flash-bang grenades being indiscriminate, targeting groups of protesters rather than individual protesters.

According to journalists and expert groups’ reports, the Belarusian security forces were armed with flash-bang grenades of Czech, Polish and Ukrainian origin: Zeveta Ammunition P-1 and ZV-6 hand-held light and sound grenades (Czech Republic), Fam-Pionki 12/70 light and sound cartridge ONS 2000 (Poland), LLC NPP Ecologist Hand aerosol grenade "Teren-6" and hand-held light and sound grenade "Teren7M" produced by a Ukraine manufacturer. Czech company Zeveta and Polish company Fam-Pionki deny selling ammunition to Belarus and claim to comply with applicable national and international regulations.

Table 4. Zeveta Ammunition light and sound grenades found after the August 2020 protests

Allegedly, the grenades were launched from grenade launchers, pump-action shotguns, or simply thrown in the direction of protesters, indiscriminately, which constitutes a grave violation of the principles of proportionality and necessity. Journalists collected evidence of the use of the flash-bang grenades against vulnerable populations: at the "March of Pensioners" on October 12, one of the security officials fired from a traumatic pistol "Wasp" - first into the air, and then towards the demonstrators. As later reported by the police, the pistol was charged with a flash-noise cartridge.

According to health sources, only from August 9 to 23, 1,140 people sought medical attention at hospitals; of those, sixty-four were wounded by fragments of military explosive devices. Victims were taken to hospitals with shrapnel wounds to the face, chest, abdomen and extremities, burns to the upper extremities and abdomen.

In line with international standards, “the use of pyrotechnic flashbang grenades directly against a person would be unlawful as it could cause serious burn or blast injuries and, in certain cases, there could even be a risk of fragmentation”. It is highly likely that the shrapnel wounds and burns, injuries of various parts of the body, are precisely the result of the illegal and disproportional use of such grenades against the protesters at close range. In addition to violating freedom of assembly and the right to life, where these weapons cause injury, such use of these types of weapons constitutes torture and inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

Later in November 2021, the same stun grenades were allegedly seen on the Belarusian-Polish border. According to a telegram channel "Belarus Brain," migrants threw the exact same grenades that were used by Belarus law enforcement police against participants of peaceful protests in August 2020 against Polish border guards. According to the channel, these were P1 grenades made by Czech company ZEVETA Bojkovice A.S. On November 16, 2021, the Polish authorities stated that the migrants were armed with stun grenades, received from the employees of the Belarusian special services. The Polish defense agency also showed a video of a certain object flying from the side of the migrants, falling and beginning to smoke. We cannot assert that it was the Belarusian side that provided the migrants with stun grenades, and it is known that the Polish side also used water cannons and tear gas against the migrants. However, these facts remain highly concerning and should be investigated.

The water cannons used by Belarus are water hoses connected to mobile tanks on trucks. They shoot high-pressure streams of water aimed at pushing back and dispersing crowds or restricting access to certain areas. "Water hoses can cause hypothermia, direct injuries from pressurised water, secondary injuries from being knocked down or colliding with objects, and injuries from chemicals and dyes dissolved in the water." Water cannons can be easily misused because of their indiscriminate character and poor targeting accuracy.

According to journalists’ reports, water cannons have been used against protesters in Belarus on several occasions, including with dyes. According to the press service of the Belarusian Interior Ministry, the Belarusian police used water cannons against groups of protesters in order to disperse the demonstrations, which, according to the authorities, "were not sanctioned". According to international law, the purpose of dispersing an assembly is by no means legitimate, moreover, the use of indiscriminate weapons against groups of individuals acting peacefully violates international standards on the use of force by law enforcement officials (see Section 1.2). The OSCE ODIHR Human Rights Handbook on Policing Assemblies is unequivocal that “water cannons should never be used to disperse a peaceful assembly”. The use of water cannons poses serious risk of injury, and indiscriminate use of the dye may lead to targeting and consequent arrest of peaceful protesters, journalists, or passers by who were marked with the coloring.

According to journalists’ reports, for the first time in Belarus during the 2020 protests, law enforcement agencies resorted to the use of water cannons. In addition to Belarus-made ones, law enforcement agencies allegedly used water cannons "Predators" produced by the UAE/Canadian company Streit Group. The water canons, according to these reports, are based on Mercedes-Benz and MAN Truck & Bus (Germany), IVECO (Italy), KamAZ (Russia) trucks. The vehicles are equipped with two water pumps with a range of 55-70 meters made by the German company Ziegler.

//water canon//

3. ACCOUNTABILITY PROSPECTS

– 3.1. Transfers violating international obligations and the EU embargo

Most of the relevant international instruments, notably, the ATT and the WA, as well as the 2008 EU Common position and EU Anti-Torture Regulation, prescribe states to refrain from issuing arms export licenses if there is reason to believe that the relevant equipment could be used to fuel human rights violations in the destination country. Considering that the situation in Belarus would have appeared to the EU member states as presenting risks of serious human rights violations since at least 2006 with the introduction of the first round of the EU sanctions on Belarus, the 2008 EU Common Position would have prohibited export of arms and ammunition listed in the EU Common Military List. This would notably concern firearms documented in section 2: the Fabarm and Benelli shotguns, SIG Sauer and Glock pistols. However, the dates of transfers are not always identifiable.

FIDH shared with the mentioned companies a preliminary version of the report, inviting them to highlight any inaccuracies mentioned in the report, as they relate to companies’ activities (see Annex 1). The Italian company Fabarm denies having any illicit transactions with Belarus and claims that “the presence, during the protests, of weapons resembling our [Fabarm] products could be lied to the presence on the market of some Turkish-made copies that are also bearing our trademark externally and which are in clear violation of our Industrial rights, but of course this is only an hypothesis”. Same allegation regarding the Turkish-made copies is reflected in a reply of another Italian arms producer Benelli: “carried out an internal audit to check whether or not there had been any exports of our products to institutions or citizens of Belarus. The result of these checks is that there have never been any exports of any kind to Belarus, either to institutions or to individuals, either before or after the embargo. The presence, during the clashes, of weapons resembling our products could be traced back to the presence on the market of external copies of our Turkish-made M4 Benelli, but this is only a working hypothesis that we suggest”.

Nonetheless, a number of European countries allegedly continued to supply arms to Belarus after 2008, in violation of EU law. One disturbing example, for instance, is a purchase in late 2011 of Swiss-German SIG-Sauer pistols for the SOBR fighters by the Belarusian Interior Ministry. These items, as documented in the section 2, were allegedly used for internal repression in Belarus. Their transfer to Belarus in 2011 would have violated the 2008 EU Common Position had the weapons been sold directly to Belarus and, depending on the exact date of the transfer, the EU arms embargo as well. It should be noted in this respect that the producing country is often not the direct supplier of the item, and there is a high chance that they were transferred to Belarus via third countries. Media reports, for instance, indicate that some EU companies tried to bypass the EU arms embargo by transferring firearms and ammunition to Belarus through third countries, for instance, Moldova.

Arguably, the prohibition under the EU Common Position extends to armoured vehicles, notably documented in the section 2 armoured trucks Mercedes-Benz and MAN Truck & Bus (Germany), IVECO (Italy), which were used to carry water cannons, and ammunition, including DDupleks 12/70 cartridge with rubber bullets (Latvia) and Traumatic 12 gauge rubber bullets (Latvia). It is not clear whether the EU Common Military List includes all the KIPs, however. Some items may be covered by various overlapping regimes: some types of the RCAs, depending on the exact substance used in the RCA, are notably covered both by the EU Common Position and the EU anti-torture regulation. Stun grenades, as the ones produced in Poland and Czech republic and documented above, for example, are most likely covered by the EU Common Position, while ammunition containing stun submunitions might not be.

Since the introduction of the EU arms embargo on Belarus in 2011, however, all the equipment used for the internal repression documented in the section 2, was banned from export to Belarus, including the equipment not covered by the EU Common Position.

Some of the items documented above appear to have been produced and transferred to Belarus after 2011. Notably, according to journalists’ reports, a stun grenade found after a day of protests, judging by its markings, was manufactured in Czech Republic in 2012. Media did also report a presence of the Belarusian vehicle on the territory of the Czech ZEVETA plant in October 2020., ZEVETA denies selling ammunition to Belarus and claims to comply with all applicable national and international regulations (see Annex 1). However, these highly concerning facts indicating that a Czech-based firm might have violated the EU arms embargo should be investigated further.

As to the water cannons, the media first noticed them on the streets of Belarus shortly before the 2015 elections. According to the media, the Belarusian law enforcement authorities have three such vehicles, each of which is a unique modification made for the Belarusian government. It appears that Streit, by manufacturing in the United Arab Emirates, is going beyond the Canadian government’s arms control regulations. Canada is a party to the ATT since 2019 and to the WA. The WA and the ATT military control lists arguably might cover vehicles designed for crowd control as they have potentially lethal consequences. These facts demand further investigation but traceability remains challenging.

The firearms market remains largely nontransparent due to the lack of binding legal instruments that encourage states to report on their small arms exports and imports and the lack of consistency with regards to serial numbers. The EU data and reporting obligations remain insufficient for having a clear picture of issued export licences and occurred transfers. This is also true for the UN Register of Conventional Arms (UNROCA), which maintains one of the largest databases tracking arms transfers across the world. Although the reporting obligations of countries under UNROCA are not legally binding, UNROCA claims to have captured more than 90% of the global arms trade, and its databases give a general idea of the extent of third-countries’ trade with Belarus.

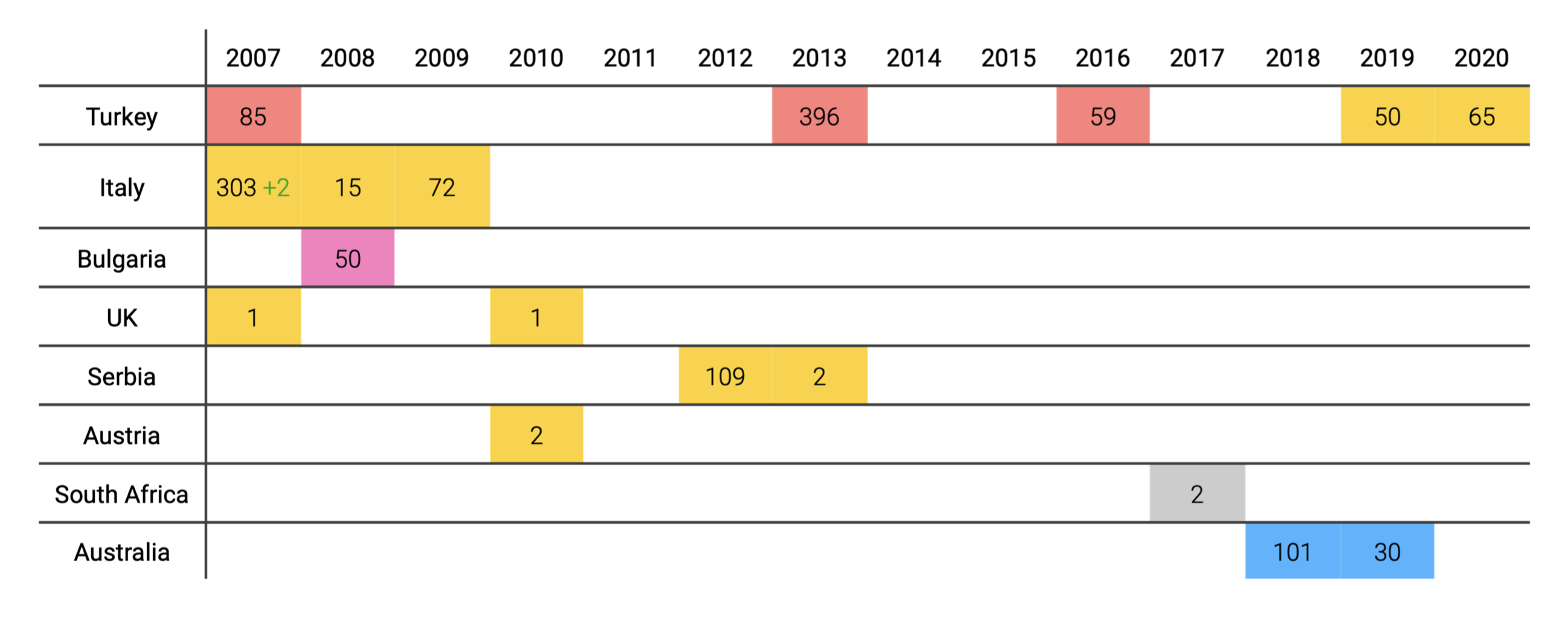

Table 5. Data on small arms exports to Belarus (UNROCA, 2007 to 2020)

According to the UNROCA database, since 2011 Belarus seems to only have imported small arms from Turkey (party to the WA, signatory to the ATT since 2013), Serbia (party to the ATT since 2014), and South Africa (party to the WA, party to the ATT since 2014). Belarus’ largest importer of small arms is Turkey. From 2007 to 2020, for which data is available, Belarus imported 540 submachine guns (it appears that mostly MP5, yet information is not fully available) as well as 115 bolt action rifles from Turkey, with the last transfer made in 2020. Belarus imported 111 rifles and carbines from Serbia in 2012-2013 and two unnamed small arms from South Africa in 2017. Australia granted authorisation for export of 131 units of small arms and light weapons to Belarus from 2018 to 2019, but it is unclear how many of those were actually exported.

– 3.2. Responsibility for human rights violations

Under international law, States can be held liable for internationally wrongful acts resulting from the breach of their primary human rights and other treaty obligations. Consequently, State responsibility may result from the breach of arms export regulations like the ATT or a dedicated ban. When applicable, the exporting countries would have had to conduct due risk assessment and refuse authorization of export if they knew that the arms would be used in the commission of violations of human rights or if an arm embargo would be breached. States could be also held responsible for facilitating violations of human rights caused as a consequence of the arms export to third states. Even if they are simply a transferring state, the state remains subject to general international law and its obligations to block the provision of material aid, such as law enforcement equipment, to a state that is known to use such equipment to commit serious human rights violations.

All relevant international and regional arms trade agreements and regimes oblige state parties to enact enforceable systems of arms export controls to ensure that transfers do not violate existing embargoes or contribute to human rights abuses. Hence, states are mandated to investigate and prosecute violations of national export control systems. However, there are currently no international legal standards regarding penalties for export control offenses. Member states of such agreements enjoy a great discretion when it comes to law enforcement of export control regulations and prosecute violators under general legislation on economic (criminal) offenses, (criminal) customs legislation or special export control legislation.

Despite the availability of legal tools to hold arms manufacturers accountable, one of the most acute problems regarding the effective implementation of export controls is the detection, investigation, and prosecution of any violation of such controls. As noted by experts, even within the EU, which has a unified export control system for military and dual-use instruments, the number of export control violations that have been brought to court is very limited.

While the accountability prospects under international and EU law are very limited and did not prove to be effective in preventing illicit export of arms and less lethal equipment or facilitating accountability for such export, corporate responsibility for human rights violations offers a complementary toolkit for preventing and prosecuting human rights violations committed by private companies involved in manufacture, brokering services, export and other operations related to arms and less lethal equipment.

Human rights corporate responsibility initiatives aim to create far-reaching obligations for businesses to provide clear information about the specific risks the weapons used in policing assemblies may pose to human rights, be transparent about technical specifications, and conduct safety analyses. According to expert reports, some manufacturers of less lethal weapons do not properly perform quality control of their products to ensure that their equipment is safe to use in policing public assemblies. Such negligent quality control can result in serious health risks to the participants of assemblies, and since no international standards are in place, it is upon companies to ensure their compliance with human rights.

Corporate responsibility is often neglected when dealing with violations of arms embargoes and arms export controls because of the competing state responsibility in issuing authorizations through export licenses. Rather than shifting responsibilities from governments to enterprises, business’ due diligence obligations entail respect for human rights as “a global standard of expected conduct for enterprises”, which applies “independently of states’ abilities and/or willingness to fulfill their human rights obligations and does not diminish those obligations.”

Human rights corporate responsibility provides a clear path for accountability as regards engaging business responsibility for exporting tools and thus facilitating the repression in Belarus. While the UNGPs do not offer a dedicated enforcement mechanism, OECD national contact points may be seized in some cases. However, these instruments remain non-binding. Yet, the current legislative movement establishing mandatory due diligence obligations in national legislations has recently opened new avenues for accountability before national courts to hold companies falling under the scope of those legislation accountable for conducting adequate due diligence, adopting all necessary measures to address human rights risks and prevent harm, as well as redressing any violations to which they may contribute directly through their operations or through their business relations, products and services.

Another path is the corporate responsibility under international criminal law, especially for aiding and abetting international crimes, that clearly emerge as a tool that can be mobilized in international law.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Although the EU export control regime, coupled with the sanctions introduced in 2011, appears to capture all the equipment used for the internal repression in Belarus, it has proven ineffective in halting all the transfers of arms and other equipment aiding Lukashenka’s regime. In view of the above, FIDH call on the European Union to:

1. Ensure that the existing embargo and sanctions regime is properly implemented, violations investigated, and the regime is not otherwise undercut;

2. Ensure that less lethal weapons are effectively covered by the EU Common Military List, and if it is already the case, clarify which types of less lethal weapons and in which cases;

3. Reinforce transparency and national reporting requirements to create possibility of a public debate at the national level around the details of the various export licenses requested, the reasons for refusing or granting them, the items and equipment in question, their description, value, country of destination, and end user;

4. Impose obligations on private companies producing arms and law enforcement equipment to conduct their own human rights due diligence, including in cases where an export licence has been issued;

5. Take swift action at the EU level to introduce arms embargoes against regimes at the first evidence of a pattern of internal repression;

6. Promote an arms embargo against Belarus at the UN level, covering all arms and equipment that could be used for internal repression;

7. Strengthen the accountability mechanisms at the EU and national levels;

8. Demand that EU Member States, in particular Germany, Italy, Poland and the Czech Republic, investigate and report on the facts indicating the potential violation by these states of Common Position CFSP/2008/944 and Council Regulation 765/2006 and its subsequent amendments;

9. To change its Common Position CFSP/2008/944) into a regulation based on article 207 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU, making clear that the eight criteria apply to items on the Military List, as well as components, related maintenance and service contracts, align on the ATT procedures, set up an independent risk assessment unit defining at the EU level sensitive destinations based on the 8 criteria currently referred in the Common position and enhance the transparency and accountability procedures, as well as the participation of civil society and European Parliament in the monitoring and assessment process;

10. Consider placing non-European companies that continue to supply the means of repression to Belarus on its targeted sanctions list;

11. Investigate private companies’ compliance with the international human rights standards and the EU law.

Similarly, the report found that global measures are not sufficient to stop the trade in arms, as well as less lethal items, including exports and imports, with Belarus. While Belarus can largely rely on domestic production of arms and related equipment or exports from Russia to continue its repression, it is nonetheless important to take urgent steps to end any contributions by other states to support the Lukashenko dictatorship. To this end, we recommend that the relevant UN mechanisms:

12. Encourage ratification of the ATT and the WA by states that are not parties to these regimes;

13. Expand the ATT and AW military lists to ensure that all equipment that could be used for internal repression, including less lethal weapons, is subject to effective control;

14. Promote the strengthening and establishment of a better reporting and monitoring mechanism to support the creation of an accountability mechanism;

15. Introduce a UN arms embargo on Belarus that also covers less lethal weapons that may be used for internal repression.

A major responsibility for addressing the human rights crisis in Belarus lies with private companies. Companies must act proactively to prevent, mitigate, and remedy human rights impacts related to their operations in Belarus, and conduct thorough human rights due diligence procedures before deciding to do business with Belarus and Belarusian companies. Until the situation in Belarus stabilizes, companies should suspend all transfers of arms and less lethal equipment to Belarus. We call on private companies exporting arms and less lethal weapons to Belarus to:

16. Immediately halt all transfers of items, including lethal and less lethal weapons and related equipment, that can contribute to the internal repression in Belarus;

17. Ensure that lethal and less lethal weapons and related equipment is designed and produced to meet legitimate law enforcement objectives and comply with international human rights law;

18. Stop transfers of lethal and less lethal weapons and related equipment if there is a risk that these items may contribute to the violation of human rights and fundamental freedoms in Belarus as well as other countries where these products may be re-exported to Belarus. To assess such risks, we recommend consulting the reports of the competent bodies of the UN, the EU and the Council of Europe, as well as the reports on the human rights situation of civil society organisations, including FIDH, Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International. Such risk assessments should be conducted including in cases where an export licence has been issued and in cases where there is no need for an export licence, cover geographically the countries at risk and those from which they are acquiring weapons, and identify potential business partners in other countries which may sell and export their products to Belarus;

19. Manufacturers should be transparent about the guidance surrounding the use of such items and make public relevant information about the risks from less lethal weapons and related equipment they produce;

20. Manufacturers should make public the information that can help improve weapons identification and traceability, including for the purpose of detecting illegal arms transfers;

21. Respect international law and the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, in particular conduct enhanced due diligence in order to identify, prevent and address human rights abuses linked to their activities, products, services or business relations.